There was None Like Moses

From the moment Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon emerged on the stage of history, the men and women of his generation, as well as the men and women of future generations, have grappled with the extensive work of the philosopher, halakhic authority and great Jewish physician. We invite you to browse the map and discover stories about the unique items that are displayed in a joint exhibition of the National Library and the Israel Museum.

Let's Begin!

-

Maimonides in Latin

Read about the item -

The Hand of God in the Mishneh Torah

Watch video -

A Bullfight in Honor of Maimonides

Watch video -

Illustrated Manuscript from Barcelona

Read about the item -

Maimonides the Philosopher

Read about the item -

“Mishnah Commentary” in Maimonides’ Handwriting

Read about the item -

A Visit to the Home of Maimonides

Read about the item -

The First Edition of the Mishnah with Maimonides' Commentary

Read about the item -

The Aleppo Codex

Read about the item -

Do Not Disturb Maimonides

Read about the item -

Maimonides Reaches Out to Yemen Jewry

Read about the item -

The Animated Maimonides

Watch video -

Maimonides Gets a Portrait

Watch video

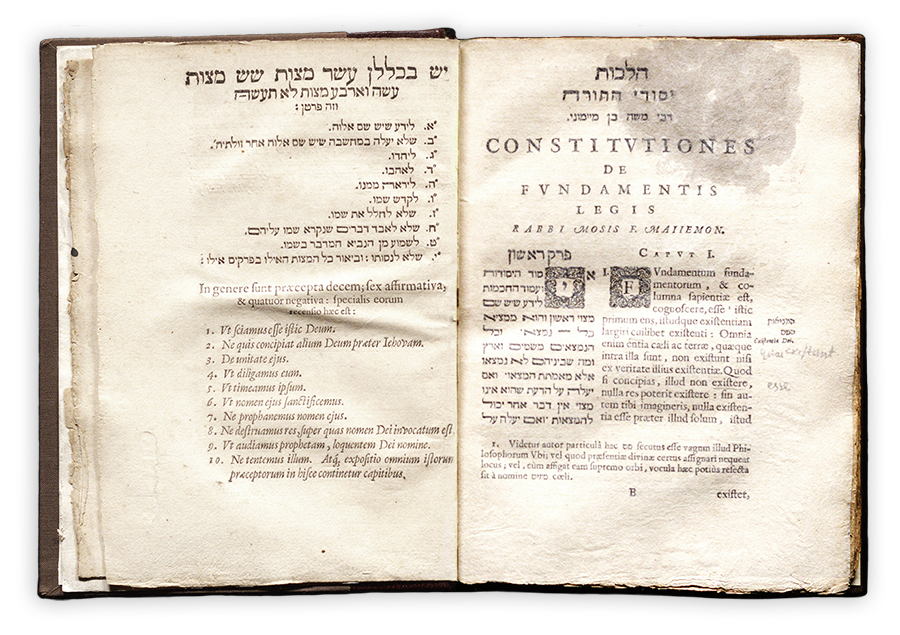

Maimonides in Latin

During the Reformation, Protestant scholars began delving into the Bible in order to find a template for a sacred political constitution. They soon realized that they would not be able to delve deeper into the teachings of the book without the help of the extensive Hebrew literature.

These scholars, called the Hebraists, "summoned" the greatest writers of the Jewish people throughout the ages to provide answers to the many questions that arose in their minds while reading the Bible. To this end, many Protestant scholars began to translate the central works of Jewish religious literature. Thus, for the first time in history, the Talmud (both the Babylonian and Jerusalemite), the Midrash, the Zohar, the writings of Maimonides, the Mishneh and many dozens of books were translated into various European languages: Latin, English, German and more. In 1638, the Latin translation of the Maimonides’s Mishneh Torah was printed alongside the original Hebrew source in Amsterdam.

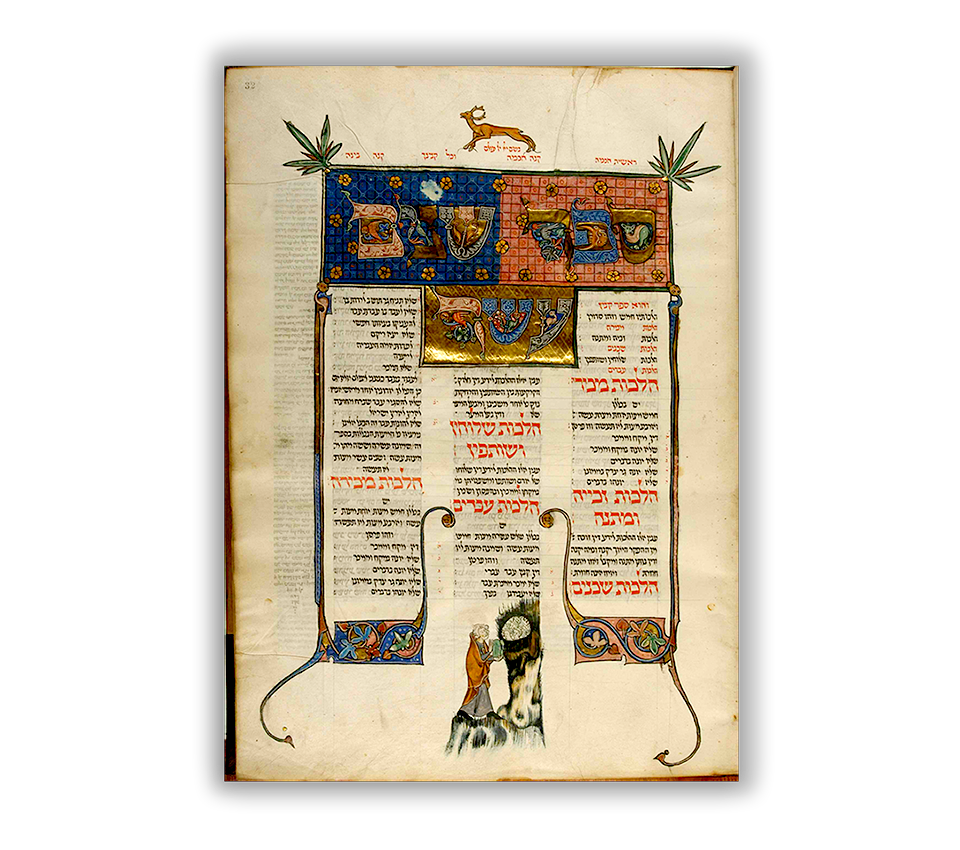

The Hand of God in the Mishneh Torah

In 1984, researcher Evelyn M. Cohen examined the biblical illustrations of Maimonides' Mishneh Torah manuscript, which is kept in the David Kaufman collection. She noticed a detail that seemed to contradict the accepted narrative. In a scene that shows Moses giving the tablets of the covenant to the people of Israel, Cohen observed another figure that was erased and hidden under a later correction.

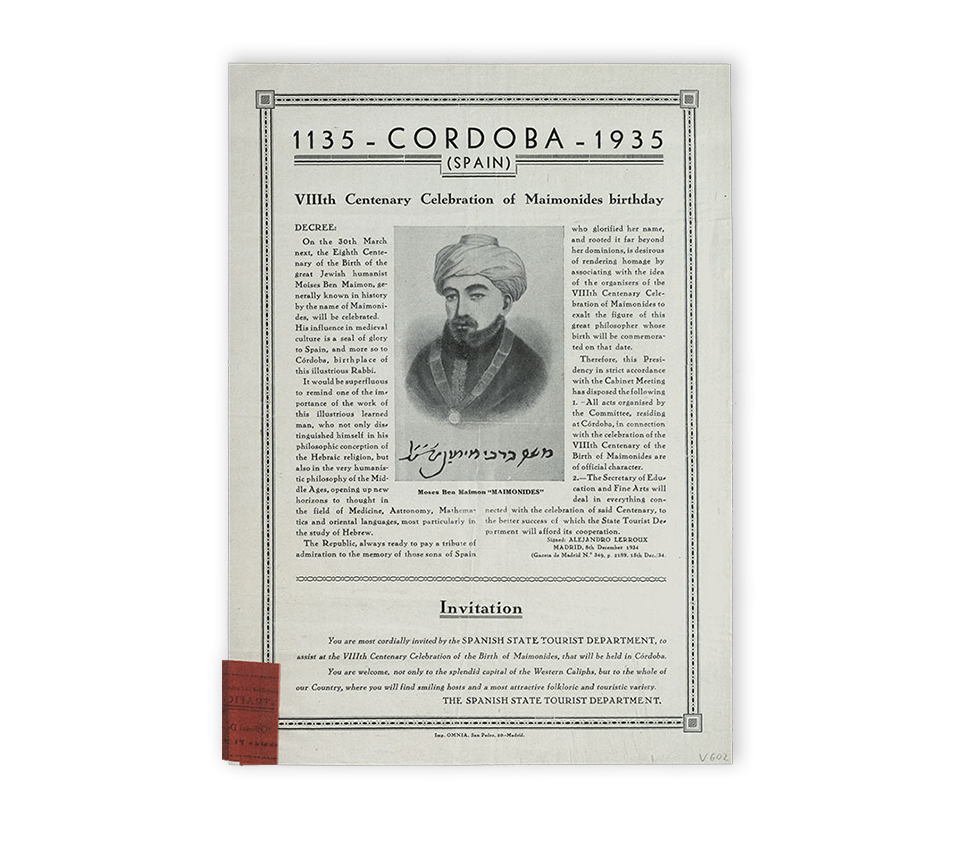

A Bullfight in Honor of Maimonides

A poster in the National Library portrays an extraordinary event: a bullfight to commemorate Maimonides' 800th birthday.

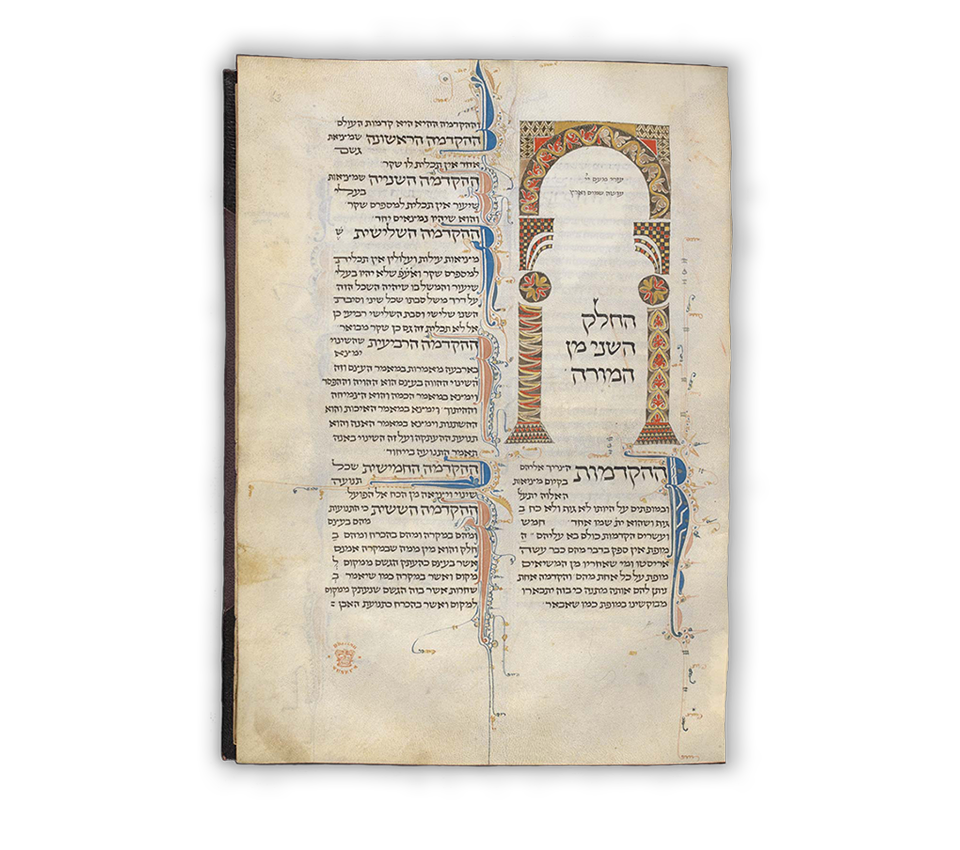

Illustrated Manuscript from Barcelona

"Guide for the Perplexed". The manuscript was copied in Barcelona in 1347-1348. Today it is kept at the Royal Library of Denmark in Copenhagen.

All that is known about this magnificent manuscript is taken from the ‘colophon,’ a short caption - usually at the end of the book - explaining who copied the manuscript, when it was copied, and (sometimes) under what circumstances it was copied. The information in this colophon is very limited.

According to the colophon, the manuscript was copied by Levi Bar Yitzhak, a native of Salamanca, between 1347-1348. The manuscript was ordered by the Jewish physician Menachem Bezalel of Barcelona, who did not enjoy the manuscript for long. One year after the manuscript was completed, the former court physician of the King of Spain passed away.

The verse chosen by the copyist to sign the colophon indicates the way in which the book was perceived in 14th century Spain: no longer an esoteric work known only to the privileged, but a philosophical guide "which Moses gave to all Israel" (Numbers 34:12).

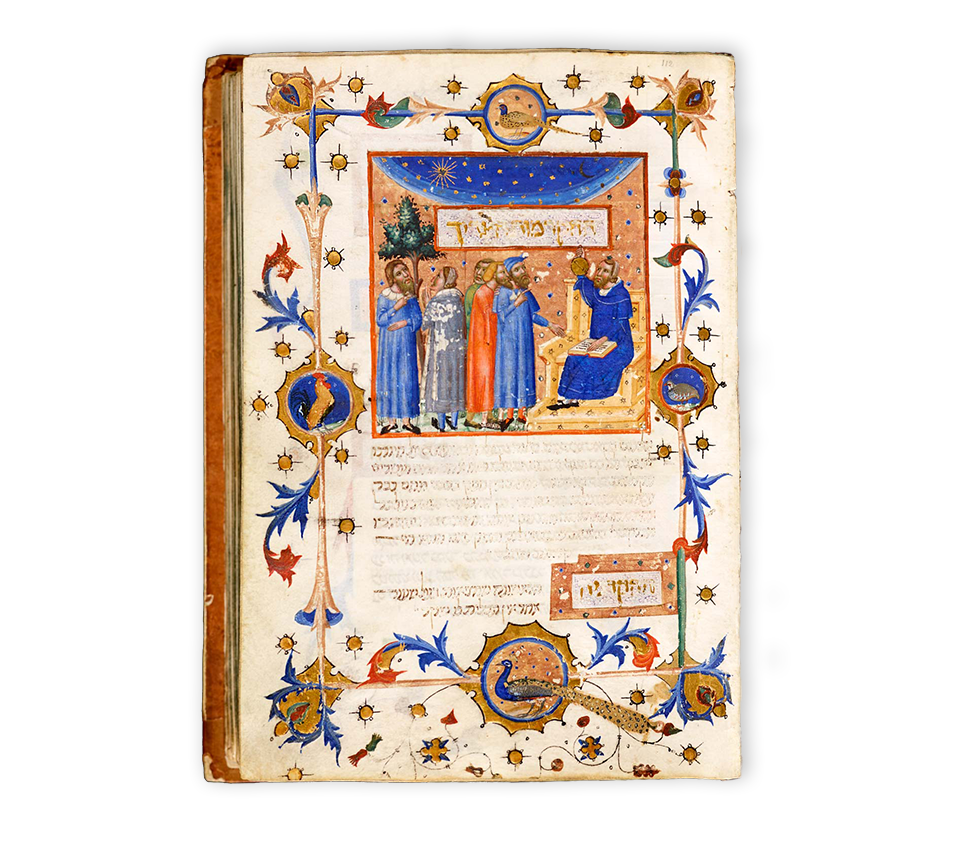

Maimonides the Philosopher

"Guide for the Perplexed" and other philosophical texts. The manuscript was written in Rome in 1283. Currently preserved in the British Library in London.

The "Guide for the Perplexed," the philosophical treatise originally written by Maimonides in Arabic, was translated into Hebrew by Shmuel Ibn Tibbon under the supervision of Maimonides. Following the death of Maimonides, the poet, Yehuda Alharizi, translated the "Guide for the Perplexed" into a poetic dialect of Hebrew. Both translations were known throughout the Jewish world.

In 1283, almost eighty years after his death, one of the first illustrated manuscripts of Maimonides' Guide for the Perplexed was copied and illustrated in Rome. Originally, the manuscript was part of a collection of twenty-three philosophical texts, most of them by Maimonides himself.

The manuscript was copied by copyist Avraham Ben Yom-Tov HaCohen and commissioned by a banker, Shabtai Ben Matityahu - both from Rome. The copyist illustrated part of the manuscript, whilst a workshop that specialized in illustration of Hebrew manuscripts painted them.

At the end of the 13th century, many Hebrew manuscripts were decorated with a special flowering pattern popular in Italy, and especially popular in Rome. Living evidence of this is found in this manuscript of the Guide for the Perplexed and other philosophical works of Maimonides that were created at the same time in Rome.

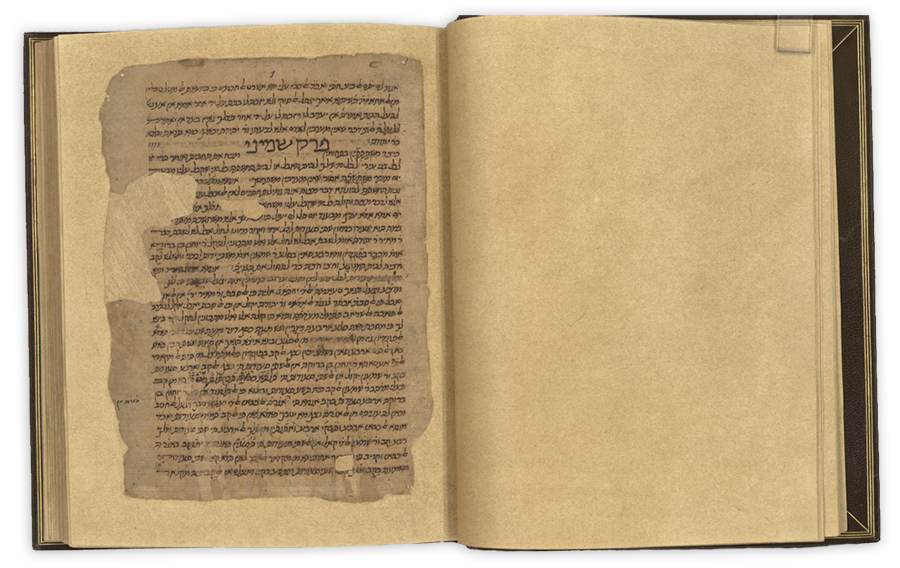

“Mishnah Commentary” in Maimonides’ Handwriting

Writing of the manuscript began in Morocco in 1161, and was finished in Egypt in 1168. Five of the six parts of Maimonides' Mishnah commentary have been preserved to this day: Seder Mo'ed and Seder Nashim are located at the National Library in Jerusalem, and Seder Zera'im, Nezikin and Kodashim are located in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

The "Mishneh Torah" was written during Maimonides' travels in the Mediterranean Basin, beginning in Morocco, where he had escaped to as a refugee several years earlier. His family had fled from his native Spain following the rise of the Almohads, a radical Islamic movement. Leaving Morocco, Maimonides traveled to the Land of Israel, where he spent five months, until he decided to resettle once again at his final destination - Cairo, Egypt. Seven years after beginning work on the Mishneh Torah, Maimonides (now 30 years old) completed his writing in Egypt.

From the moment the commentary was published (two years after his arrival in Egypt) Maimonides assumed the role of leader of the Jewish community in Egypt. The completion of the Mishneh Torah marks, in terms of the history of the Maimonides, his transformation into a well-known and recognized leader of the Jews of Egypt in particular – and the Jews of the East as a whole. Maimonides inscribed his book with the following apology:

"We have already completed this work as we have intended, and I seek His forgiveness and beg Him to save me from mistakes. And whoever finds a place of doubt in him or who clearly sees the halakhot in a better light than what I have explained, must comment on this as is his right. Because what I have imposed upon myself is not a small matter, and it is not easy to perform as a righteous person with a sense of good discernment. And since my heart is often preoccupied with the ravages of time and what the Lord has decreed upon us in the exile and wandering in the world from the end of heaven to the end of the heaven - perhaps we have already received this reward of exile as atonement. He knows that He will be exalted because there are halachot which I have written while on journeys on the roads, and what are the matters of the martyrs when I am on the ships in the great sea.”

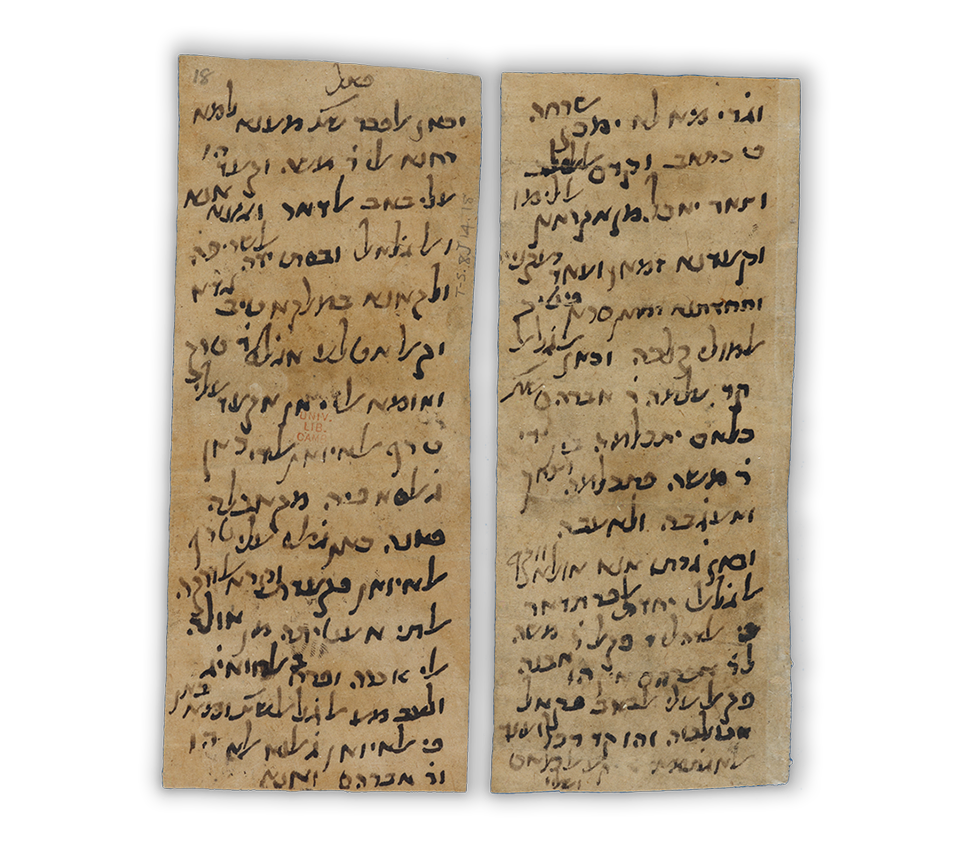

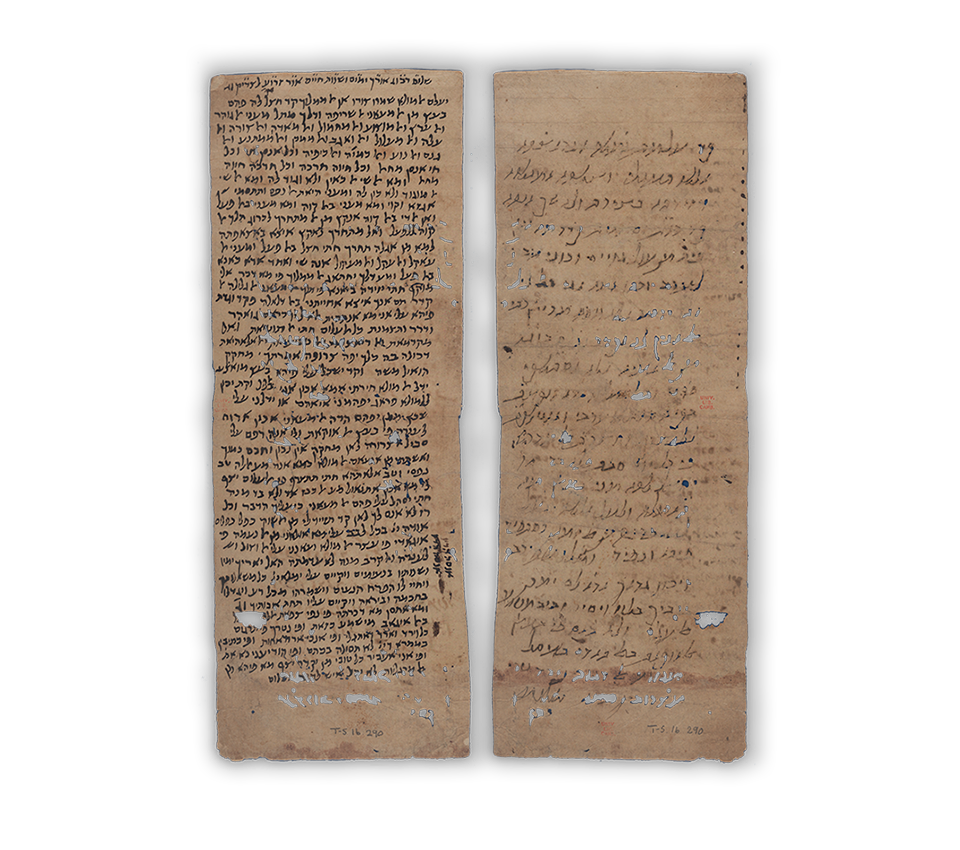

A Visit to the Home of Maimonides

Letter from Cairo Geniza, 12th century. The letter is currently stored at the Cambridge University Library, in the Taylor-Schechter Cairo Genizah Collection.

In one of the more fascinating writings of the Cairo Genizah related to Maimonides, a Jewish man tells of a meeting that took place in Maimonides' home many years earlier. At the time, the writer was asked to pass a private correspondence to Maimonides, which he believed would take only a few minutes.

To his surprise, the messenger was invited to Maimonides’ room together with his son Algalal. Maimonides opened the letter, read it, and even asked his opinion. Abraham, Maimonides’ son, was also present in the room. Maimonides sought to expose him to the business of public leadership from a young age in order to prepare him for the future.

While the adults were talking business, the two boys had a funny conversation between them. Abraham taught Algalal one of his father's illustrious references. A good spirit prevailed over the entire meeting and Maimonides, who listened to the boys' conversation, was greatly entertained with Algalal.

Maimonides did not grant a public position to his son, but his investment paid off. After his death, Abraham stepped into the position of leadership that Maimonides had held in his life and became an important thinker and great Halakhic authority in his own right.

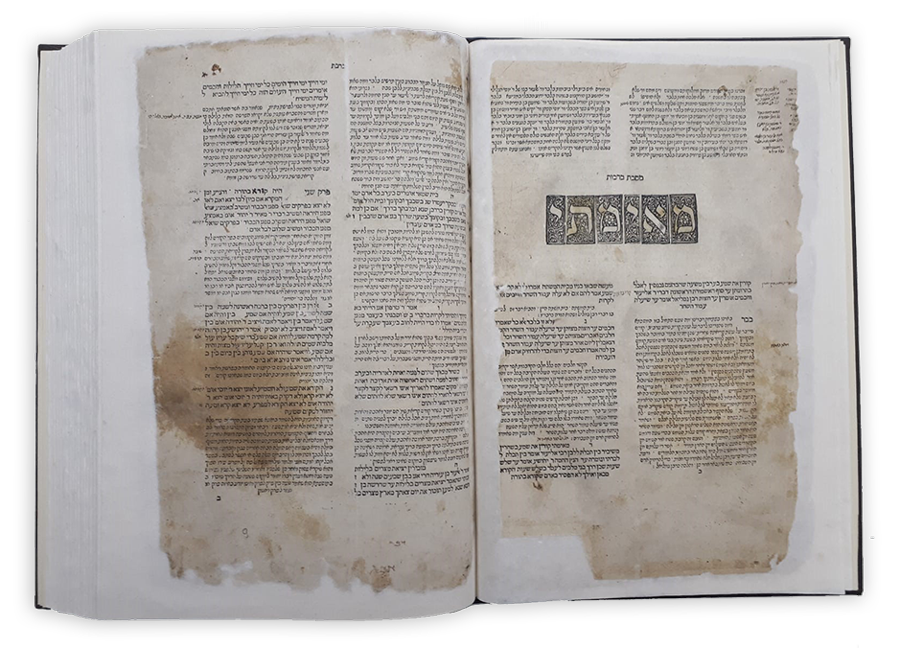

The First Edition of the Mishnah with Maimonides' Commentary

First printing of the Mishnah with commentary by Maimonides, printed in Naples in 1492. A copy of the book is preserved in the National Library of Israel.

The Maimonides hoped that the reader would find in his book all the rulings and halakhot necessary to maintain a full Jewish life.

The first edition of the Mishnah with Maimonides’ commentary was published in Naples, Italy in 1492, the same year in which the Jewish population was expelled from Spain. Already, in the early days of printing in Hebrew, an “Achilles' Heel” was discovered within Maimonides' great exegetical project: Jewish scholars refused to abandon the engagement of Talmudic argumentation and controversy.

They turned the work of Maimonides into yet another layer in the vast interpretive literature that he himself had sought to summarize and distill.

The copy of the work that resides in the National Library contains notes in the handwriting of the annotator, Rabbi Shmuel Lirma.

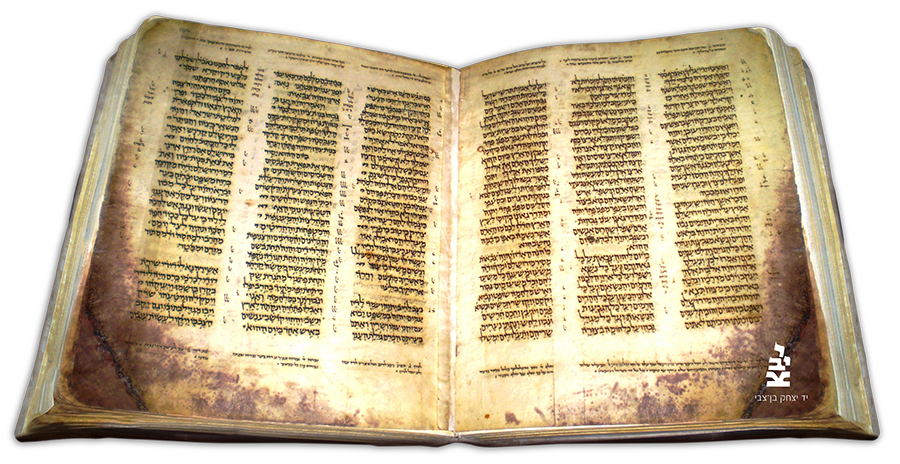

The Aleppo Codex

The Aleppo Codex was written in Tiberias around 930 CE. The manuscript is located in the Israel Museum and is owned by the Ben-Zvi Institute of Jerusalem.

The Aleppo Codex is the oldest known manuscript of the Bible that has been preserved in its entirety. The text of the Bible in the Aleppo Codex was copied by the author, Shlomo ben Boya. At the end of the work, the Masoretic scribe, Aharon ben Asher, added the three components of the Tiberian tradition: vowel points, cantillations and Masorah.

It is generally accepted that the wording of the Aleppo Codex is the most precise version of the Bible we have in our possession. Both traditional and historical research have confirmed that this is almost certainly the manuscript that Maimonides used when writing the Mishneh Torah. The Rambam said: "And the book that we relied upon in these words is the well-known book in Egypt, which includes four and twenty books that were in Jerusalem for several years from which the books were proofread.” (Maimonides, Hilkhot Tefillin and Mezuzah and Sefer Torah, chapter 8).

The Aleppo Codex was kept in Jerusalem until the Crusaders captured the Holy Land. It was taken by the Crusaders and sold in the slave market in Ashkelon. The Aleppo Codex was eventually bought by the Jewish community in Cairo, where Maimonides came in contact with it. It was later transferred to the Syrian city of Aleppo by the rabbi's great-grandson. It was preserved in the Great Synagogue of Aleppo until the Israeli War of Independence. In 1957 it was smuggled out of Syria with the assistance of the Mossad. The Aleppo Codex was transferred to the authority of Mr. Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, the second President of the State of Israel.

Courtesy of the Ben-Zvi Institute, Photographer: Ardon Ben Hama.

A Doctor Named Rambam

Rambam Medical Center – Haifa, Israel. The hospital was inaugurated in 1938.

After the unexpected death of his brother, David, in the Indian Ocean in 1177, Maimonides experienced a terrible health crisis. For a year, as he testifies in a letter addressed to Yefet Dayan that was found in the Cairo Geniza, he “fell on the bed with bad boils and inflammation, and I was almost lost.”

Until his death, David was the breadwinner of the family. This enabled Maimonides to dedicate himself entirely to community affairs and to writing the Mishneh Torah. Before the disaster, as a young man in Spain, he had achieved a reputation as an expert in the medical profession.

An important and necessary profession, it enabled the Rambam, a perpetual refugee, to find a livelihood in every country he found himself in. He subscribed to the thinking that in order for a person to gain the knowledge of God and the world, as complete knowledge as one can attain, he must first take care of, and repair, the expendable body given to him.

This important aspect of Maimonides' life and work has been honored by many entities. The most significant of these is the establishment of the Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, the largest medical center in northern Israel.

Do Not Disturb Maimonides

The proliferation of printing enabled not only the mass dissemination of Maimonides’ writings, it also gave him a face. Or, more precisely, lent him a portrait that people could associate with him.

Along with the familiar obstacles that stand in the way of work of every creator, there are concerns that are not often voiced as well, first and foremost – the fact that people tend to take advantage of the author's attention to advance their own goals. Maimonides knew this obstacle well and did everything in his power to overcome it.

Among the thousands of fragments found in the Cairo Genizah are dozens of letters between Maimonides and communities and individuals throughout the Jewish world, most of which deal with Halakhic (though sometimes medical and scientific) issues, in which Maimonides was asked to rule or to express his opinion. In recognition of his status, the Rambam responded to these requests – albeit in uncharacteristic brevity.

In the attached Geniza letter, we see another type of request that Maimonides almost always refused: a request for a meeting. One of the letters sent to Maimonides was written by a person interested in deepening his philosophical studies and seeking a suitable guide. The writer notes the great interest he found in the ‘Guide for the Perplexed,’ and asks the great thinker whether he would agree to meet with him or, alternatively, to recommend someone else to help him understand parts of the "Guide" that he did not understand. In addition, the writer asks Maimonides to recommend a suitable diet that will help him withstand his intellectual activities.

Maimonides' response, which was written at the bottom of the letter, is his routine response to requests of this kind: because he is sick, tired and frail, he does not have the time or energy required for such a meeting. The few moments he can devote to the writer are on Shabbat in the Beit Midrash. He recommends eating almonds, raisins and date honey.

The letter itself is not dated. It is tempting to determine, judging by Maimonides’ answer, that it was written towards the end of his life. But since his response to those interested was a fixed version - it may have been sent several years prior.

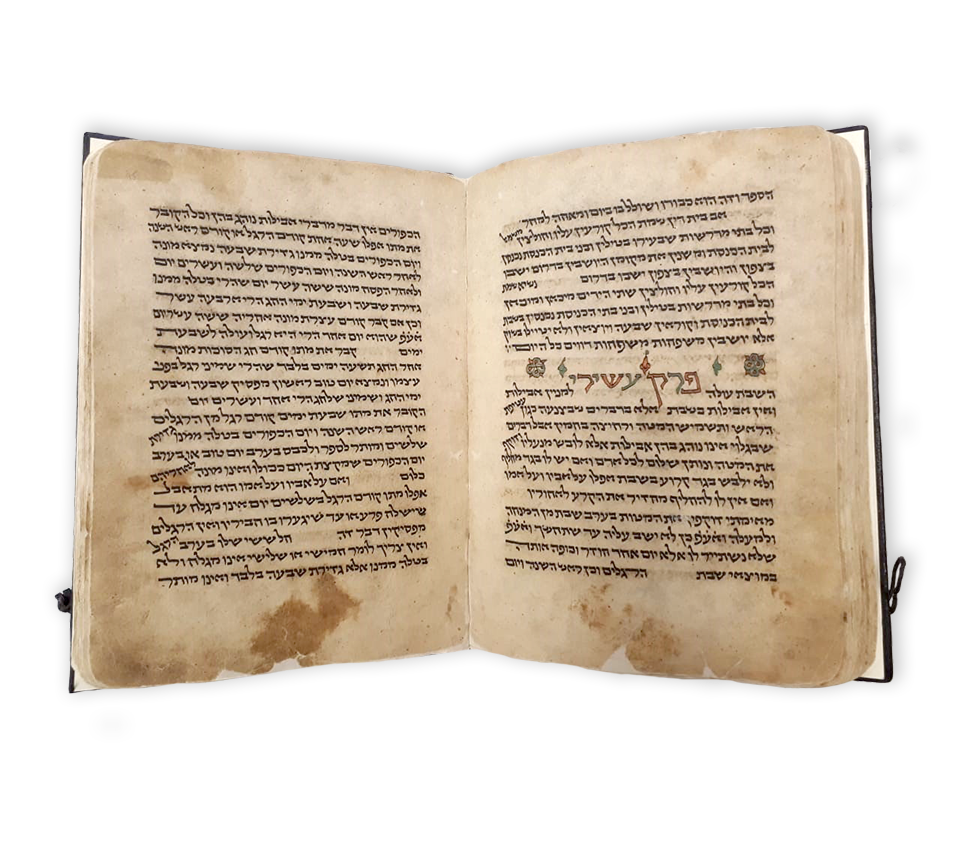

Maimonides Reaches Out to Yemen Jewry

Sefer Shoftim from the Mishneh Torah. The manuscript was copied in Yemen in 1433. The manuscript is currently housed at the National Library of Israel.

The relationship between Maimonides and Yemenite Jewry is well documented even from the time of the Rambam himself. In his mid-thirties, the Jewish governor of Yemen, Rabbi Ya'akov ben Netanel, contacted the Rambam in the wake of the severe, ongoing persecution suffered by Yemenite Jews for twenty years. Well aware of the possibly dangerous implications, Maimonides dispatched the “Yemen Letter” in 1172, offering his religious, moral and humanitarian support.

The frequent incidences in Maimonides' writings are a testament to the complex relationship between himself and Yemen Jewry: Among the texts of Yemenite Jewry, the writings of the Rambam are considered a genre of their own and are treated with extraordinary attention.The manuscript of Sefer Shoftim from the Mishneh Torah, which is kept in the National Library, is a living example.

The Animated Maimonides

A children's film about Maimonides, produced by the Hidabroot channel with the Destiny Foundation.

In the digital age, the character of Maimonides continues to maintain its larger than life complexity: a doctor, a philosopher of world influence, a Jewish reformer and a halakhic authority - any given application or website about the Rambam can choose to focus a different aspect of his character.

YouTube hosts an hour-long animated film based on an illustrated children's book, "The Rambam: The Story of Rabbeinu Moshe Ben Maimon" was authored by R. B. Avrech and illustrated by Ludia Solop and Svetlana Pakarovski. It seeks to make Maimonides accessible to children through the story of his life, including a focus on the tragic death of his brother, David, and the ramifications of this disaster on his life.

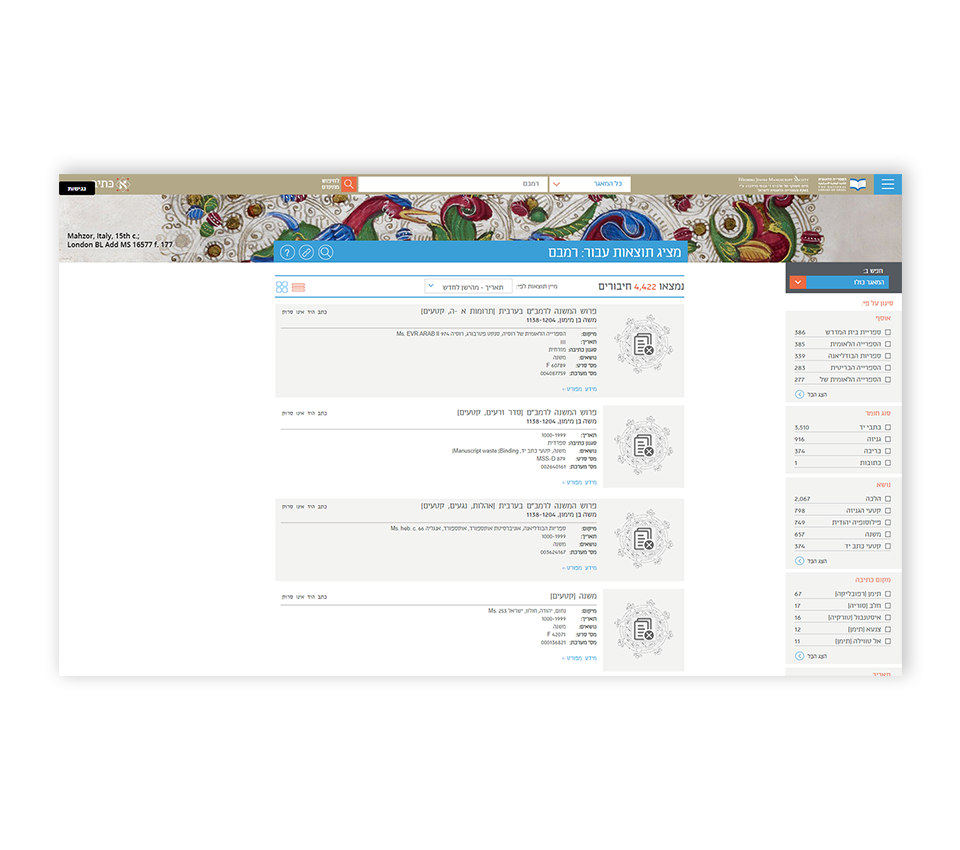

All of Maimonides' Manuscripts on One Site

The "Ktiv: The International Collection of Digitized Hebrew Manuscripts" website of the National Library. The site went online in 2017.

As part of the establishment of the "Ktiv" website: the International Collection of Digitized Hebrew Manuscripts, thousands of Hebrew manuscripts from universities, research institutes, libraries and private collections have been scanned and uploaded to the web. Maimonides has a central presence on the site.

At the time of this writing, a search of Maimonides will yield 4,781 independent results in the database. The National Library of Israel is graced with 376 items - all manuscripts - related to his work: the Mishnah commentary, copies of the Rambam’s works and manuscripts explaining his teachings.

The Daily Rambam

The Daily Rambam website. The project began in 1984, prior to the appearance of the internet in Israel.

The Daily Rambam project’s website was established for the sake of those who wish to maintain a constant relationship with the Rambam and his teachings. In the "About Us" section of the website, one can see a glimpse of the vision behind the ambitious project: Since Maimonides was the only one to encompass all the halakhic issues that are found in the Oral Law, the "Daily Maimonides Study Path" enables "the study of one chapter per day and stretches over two years and ten months (a total of 1,000 chapters)”.

There is an app version of the project, and also - because it wouldn’t be complete without - printed textbooks with commentary by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz.

Maimonides Gets a Portrait

The proliferation of printing enabled not only the mass dissemination of Maimonides’ writings, it also gave him a face. Or, more precisely, lent him a portrait that people could associate with him.